So… I was considering writing my own artist’s manifesto on this blog. This would be outside the realm of anything I’ve done on this blog. What my readers come to expect is a review, often with a more analytical bent, that critiques a piece of art. I have focused largely on the cinematic arts (which I know little about) and music (which I know more about). The rhetorical analysis I did of Eisenhower’s Military-Industrial Complex was probably the most left field thing I’ve done, but even for that I was going to turn my lens to stand up performers like George Carlin and Richard Pryor as part of a larger “Great Speeches” series. It would still fundamentally be about entertainment, even if it had the flexibility to cover significant historical moments that inform the current moment.

I figured, if I wrote anything like an artist’s manifesto, I would start a new series called “Free Form”. The title is self-explanatory. These have no form and the title is a signifier that what follows is not explicitly connected with the rest of the content on this blog.

Understand while reading this that I went in with the best intentions. I sat at my laptop and thought long and hard about what my manifesto would say now that I am at the end of my undergraduate college career. I sat for a minute that became an hour. That hour became two. Three. Some of my thoughts around this time revolved around the fact that what I thought to write was already out there. I put it out there a little more than three years ago to the Davidson Foundation when I was selected as a Davidson Fellow, where I received $10,000 for my project titled “Music as Voice: Presenting the Mosaic of Life”. That money has been important to me many times in my studies.

I thought I might draw on that to write my current manifesto. Then I thought to myself, that was 4 years ago, certainly some things have changed since then. I might start a new blog that is more focused on my personal thoughts about my art. This blog is a way for me to write about things that interest me, for better or worse.

When I couldn’t come up with anything that was relevant to me right now, I decided to do research on the great Artist Manifestos of the past. All my research pointed to F.T. Marinetti’s The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism. Everyone said it was foundational, one of the first and one of the best. Upon reading it, I immediately felt that it was revolutionary in an antiquated way that, considering the current moment, is a bit dangerous. To eschew history and suggest that your prized creations are as disposable as that history they eschew is simply wrong. The way we live right now is the totality of thousands of years of modest improvements made by our distant ancestors. The irony of futurism’s dismissal of the past, as rendered by Marinetti, is that they throw away everything that has afforded them their comfort in order to seem bold. This is dangerous because to ignore history is to risk repeating the same mistakes others made. As outlined in Sir Glubb’s paper Fate of Empires, empires and significant countries whose growth resembles that of empires have a life cycle that is little understood. Even though this article uses rather arbitrary dates to fit certain empires into his 250-year life cycle theory, it does remind that history shows remarkable consistency in the way great nations fall apart. All of this to say, I did not identify with what Marinetti had to say. I also greatly disliked the writing style, which I thought to be pointlessly descriptive and quite ham fisted. I would list specific examples, but there is still plenty to go and I’ve already gone on quite long.

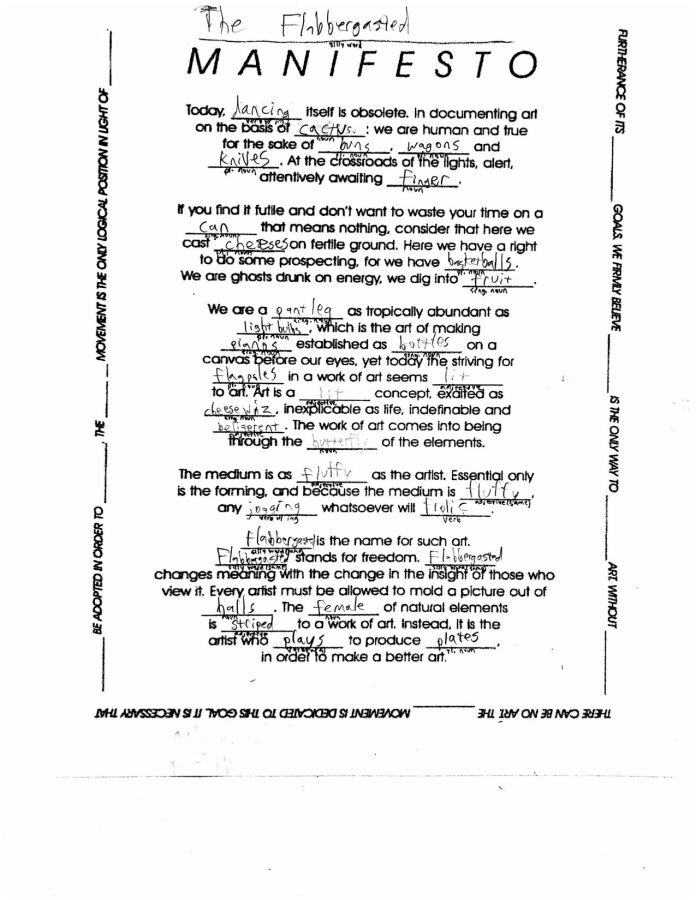

The important thing is that, in my research, I ran into Michael Betancourt’s The _________ Manifesto. Betancourt is a film theorist and historian who dabbles in critical theory. (Fun fact: He is alumni of the school my sister is attending, Temple University.) I had a good chuckle when I saw his blank manifesto and printed out some copies to play a Mad Libs style game with my friends. What this manifesto did brilliantly was, in my mind, parody the formula Marinetti helped create. A bold statement of intent that has become formulaic after the many iterations it has gone through. The form I asked people to fill out looked like this:

I personally inserted the parts of speech in order to ask people for words in a way that they are familiar with. To get responses, I went to Bursley Dining Hall and talked to one of my friends, until I got a reminder on my phone telling me to go to a studio mate’s recital. As an aside, I really enjoyed her recital and she gave a committed performance of one of my favorite pieces in the euphonium repertoire, Concert Variations by Jan Bach, look for Amanda’s Senior Recital for the complete livestream. I got some interesting responses, after her recital. My personal favorite response came in this stretch (it was co-authored by two of her collaborators):

Now, this Mad Lib game is as much a tool for recruiting viewership to my blog as it is a fun way to start brainstorming about what I might say in my new manifesto. So, I decided to fill out this form with my own answers, not bound strictly to the Mad Lib format, and expand on it with my own ideas about what my artistic intentions are. Here is my manifesto for the time being. It is more of a freewrite inspired by Betancourt’s blank manifesto:

Today, Western Art music itself is in trouble. In documenting art on the basis of tradition, such as the Western tradition: we are human and true for the sake of expression and continuity. Expression is something that unites all artists regardless of discipline. The ability to communicate genuine emotion through art is the most important skill any artist can develop. What can become the enemy of this, for purveyors of Western Art music, is continuity. Continuity is often realized through the emulation of previous performances that we deem definitive by a master whose interpretation we treat as gospel. There is a temptation in carrying on tradition by simply emulating. Desmond Richardson, addressing a room including myself and other promising arts students, said, “the good artists in this room will continue doing what has been done, the great artists in this room will change the way things are done.”

I have thought about this for the better part of a decade now and I wonder less about what will make me great, but what I can do today that will redefine the way my instrument is played. If I learned anything in college, it is that these answers don’t come easily and they need to be explored continuously to bear any meaningful fruit. I play the euphonium. It is a beautiful instrument with a sonorous, sweet sound that, unfortunately, few people know about. I view myself as an ambassador for the instrument as well as the tradition it represents, Western Art music. Though the euphonium is relatively new in the history of Western music, invented in 1843, the warm sound of the instruments allows it to perform works that predate the instrument’s invention as well as works written for the instrument. Bassoon music translates especially well to the euphonium. I have performed transcriptions of three works written for bassoon (two works by Mozart and one by Hummel), and they have been successful in recital programs.

However, choosing repertoire that predates my instrument’s creation is not itself revolutionary. People of previous generations often played arias and solos written for other instruments, especially before the repertoire boom headed by British euphonium soloists such as Steven Mead and the Childs dynasty (Nicholas, Robert and David Childs).

I don’t have a definitive answer for what will change the euphonium, but I have sought to bring my instrument to new places and educate others about the broader implications of their art. In the past, I have been a member of music communities that do not usually include euphonium, for the Friday Morning Music Club to the National Symphony Orchestra’s Youth Fellowship. I have also taught courses that teach STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math) concepts via the arts, especially music. This may be my proudest achievement and the aspect of my artistry that can yield the biggest change. Education is such a foundational building block in civilized society and this fusion of subject matter allows children to integrate their creative spirit and their intellectual spirit. To summarize…

1. Expression and continuity are the cornerstones of music making, but never let continuity become the enemy of expression.

2. Great artists serve to revolutionize their fields by combining expression and continuity. Good artists serve continuity.

3. Education is a foundational pillar of civilized society. By integrating my art into the way I teach, I am fusing the creative spirit and the intellectual spirit to create a more complete student. (This is my greatest achievement even if it is not entirely my revolution.)

This has been an interesting task. In the end, this type of thinking about my art might be the foundation for another blog that is more directly focused on my art. Let me know what you think in the comments. Thank you for reading this VERY free form post.

A few years ago, I saw Julian Rosefeldt’s movie(s) Manifesto https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manifesto_(2015_film) shown on multiple screens that I could walk between and linger over in the Park Avenue Armory in New York. I was most taken with the ecstatic language for which all the manifestos in these movies strive, like artistic sermons–really works of art in themselves–perhaps attempting to suck the passion from the core of the art forms and genres they attempt to define and direct, while shattering them in order to make them fresh and new. And there were a few manifestos–with I suppose the realization of the efficacy of other, past, and therefore presently in-need-of-being-overdone manifestos–that attempted to capture the futility and arbitrariness of crystallizing artistic passion in words and a moment.

In your manifesto (in progress), you realized this distinction, explained it well, and posited a way to transcend for yourself.

I came close to writing a real manifesto a few times, but none of my attempts came close to one that a friend of mine from college actually did write–even without setting out to write one. In fact, it was an inspired letter to me (really to him) on oversized paper on which he filled the page with advice about artistic creation, and somehow the spirit spoke through his pen. The line he wrote in his manifesto that I remember most is: “Do sketch the line of what you are / ever so slightly with a minor thing.”

I’m looking forward to seeing what forms as you sketch the line of what you are.

LikeLike